I used Midjourney AI to hack what I think our cars should look like

As much as I enjoy writing about cars, I had originally wanted to be a car designer up until halfway through high school, in grade 10 or so.

At some point, I remember thinking my drawings weren’t great (or at least I wasn’t prepared to put in the effort to make them better), and I convinced myself I’d be better as a writer and photographer than a car designer.

In more than two recessions since that time, I’ve learned that journalism isn’t the universally valued, stable profession I thought it’d be, and that even drawing door handles for a major automaker would keep my wife and cat worry-free when it comes to my employment.

Problem is, I’m only a few months into using Artificial Intelligence (AI) and I see how it could dramatically change how cars are designed, built, and marketed. If it’s time for a career change I can grow old with, my choices might be between delivery or operating some kind of AI.

At this point, I’ll assume you have some basic knowledge of Artificial Intelligence (AI), and if not, start with this excellent explainer at NewScientist.

(I will stay clear of the ethical implications of forcing millions of people around the world to shore up their savings and resumés in the face of gradual obsolescence and unplanned career changes.)

Over the last few days, I’ve been experimenting with Midjourney AI’s /blend function. It’s a simplified version, meant for mobile users, of functionality built-into the image-generation tool that can combine two images.

Each time the function is run, Midjourney delivers four smaller “sketch” images, with a choice to upsize any/all of the four or to create variations of any/all.

Right now, every time a prompt is run, there’s potential for elements to “hallucinate,” the term we use when AI creates a fake, undesired, or uncalled-for result.

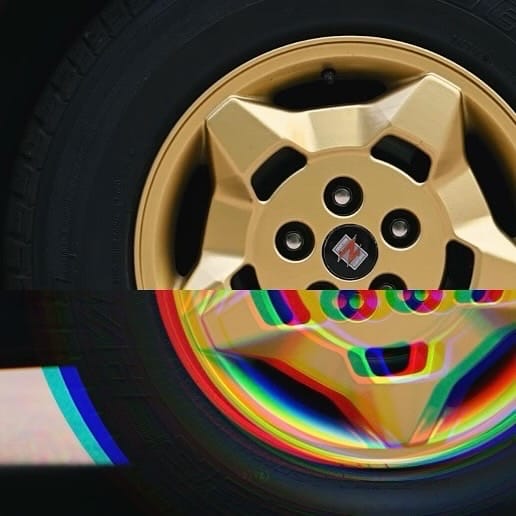

In my case, upsizing an image can sometimes leave bloopers, commonly:

- the vehicle’s rims are oddly-shaped;

- an uneven number of side mirrors;

- asymmetrical attributes;

- rear spoilers to nowhere;

- jarring colours;

- ugly proportions;

When I like where one of the smaller generated sketches is going, I keep iterating—like pulling the lever on a slot machine—in the hope I’ll get a compelling result. Sometimes, a blend looks good enough for social media after three iterations…sometimes, it takes 10-15 tries.

Compared to a real automotive designer, I’m doing the blends quickly and not trying to refine a design or specific details over a long period of time.

Again, this is early days for this technology and I’m not employed in an automotive design department where I have time to experiment with this.

I think that within a few years, we’ll have similar image-iterating functionality built into apps that run on mobile phones, computers, and tablets like the iPad.

Rims oddly-shaped? Select them, drag over a new reference image of some classic BBS centre locks, and tap: an AI will merge the new wheels onto an old cube. A specific line needs refining? Draw one in. The modeler is creating files to feed into the 3D printer? Extrapolate dimensions, use AI to stitch together front and rear views, and print it out in resin by lunch.

Even now, generating each creation is pretty basic.

It’s done through a text prompt: I type /blend, I’m asked to supply two reference images, and I submit them to be blended.

However, it’s time-consuming. As stated above, at any stage, Midjourney AI doesn’t know what I like or don’t like about each image, so I’m stuck pulling the slot machine lever until I get lucky.

In a few years, AI-supported functions across applications of all types will blur the line between man and machine creator that many people will stop wondering what is and isn’t human—they will be most concerned with what is.

For every beautifully-rendered design sketch, there will be a middle manager at an automaker who, in an argument, pulls out their tablet and uses AI to generate “better” taglines than the in-house team of AI-supported copywriters. Or maybe a board member suggests a limited edition model, with sketches made by AI the night before, over drinks.

U.S.-based supercar manufacturer Czinger already has AI woven throughout its operation, using software to help iterate mechanical components until they’re stronger, lighter, and more effective.

Then, Czinger uses 3D printing to quite literally build parts from nothing—including the gearbox for its upcoming 21C hypercar, a world first. Partnering with gearbox specialists Xtrac, the Czinger high-performance automated 7-speed gearbox is made without tooling, and is instead created using 3D printed castings using a proprietary aluminum alloy.

In a world where upstart manufacturers are busy with world firsts, it’s not tough to think of how home mechanics who are in need of a brake line in specific dimensions could one day print out a new one.

The small stuff is perfect for this technology: trim clips, plastic pieces, mounting brackets—maybe with the help of AI, we could print out a brand-new part after supplying a few cell phone photos of the broken one.

Bodykit manufacturing, ecomodding, aftermarket performance parts suppliers—heck, I wouldn’t be surprised if it’d be possible to one day download a few files and add an official Shelby rear spoiler to a late-model Mustang.

Today, companies like 3DFY.ai are working on technology to extrapolate 3D models from 2D images. I suppose that in a few years, designing, printing, and shipping items like custom diecast toy cars will be easier than it was printing digital photos out at the drug store was 10 years ago.

These /blend images are fun, but what happens when a wealthy car collector decides to do it for real—like they have been doing for decades through the special projects departments at companies like Rolls-Royce, Ferrari, and Porsche? Does the world simply accept that it’s possible to create a legitimate AI-designed road or track car out of thin air? Who checks to see if the source material was used with permission and not reverse-engineered from elsewhere?

Crucially, how does a designer make a name for themselves when their talents will at some point need to interact with AI tools? Will it be a scandal if future “human-designed” vehicles are found to have had AI assistance in their construction? And who gets the credit when things go well?

I don’t know—I’m only a few months into using AI tools, seeing others’ work, and experimenting with what’s possible.

Member discussion