Citroën Coccinelle and Hello, it's CES

Are you familiar with André Lefèbvre?

With a career that started at revolutionary boutique automaker Avions Voisin and finished at Citroën—where he earned 10 million sales for the double chevron during his tenure—it’s easy to spot Lefèbvre’s fingerprints if you know where to look. Consider his track record: the Citroën Traction Avant, HY van, 2CV, and DS were on sale for a combined 119 years. All four were pioneers, often first with attributes and features we take for granted today.

The monocoque chassis. Standard power disc brakes. The front-wheel-drive sedan. Semi-automatic transmissions.

Before his groundbreaking work with Citroën, he’d won the 1927 Monte Carlo Rally. He invented the retractable hard top. And he designed a race car with a water pump driven by a propeller to save on parasitic losses(!).

Lefèbvre is best described as an engineer with a talent for driving and an eye for aesthetics. He worked in concert with his friend, former sculptor and car designer Flaminio Bertoni, who always found novel solutions for styling Lefèbvre’s ideas.

With the Coccinelle project, however, Lefèbvre went it alone.

His idea was simple: the humble 2CV had been designed for rural areas. With its 425-cc engine and performance suited to speeds of 65 km/h (40 mph) and less, not to mention its radical simplicity, the 2CV was increasingly out-of-place as highways were built and economies recovered after the Second World War.

Citroën had the DS as its top-of-the-line model, but nothing between it and the 2CV. Enter the Coccinelle.

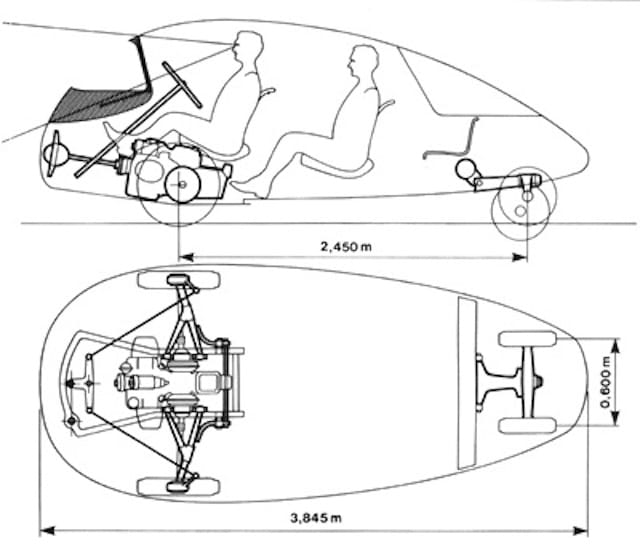

The project started in 1953 with Lefèbvre, two engineers, and two technical draftsmen. Like usual, the master would ask the impossible of his team: an ultra-light, aerodynamic sedan with room for four and their luggage…that they could drive across France for vacation.

Pray we don’t need to live through two world wars, as Lefèbvre did, for our engineers and automakers to rediscover the idea of intelligent, deliberate — clever — austerity.

Intended to be an ultramodern design, the team used complex calculations to determine its overall shape, intended to honour both a raindrop and its namesake, “La Coccinelle,” the ladybug. Like always, Lefèbvre didn’t do it half-assed. The chassis was a tub-like curved sheet aluminum hull, strengthened with cast alloy in sections; chassis parts were then glued together—a similar construction method would later resurface in the Lotus Elise.

Plastic body panels opened for the gull wing doors (and conventional lower doors) and the windshield was made from Perspex. This strong but easily marked material meant that the car couldn’t be fitted with wiper blades…so another novel solution was needed. By tweaking the aerodynamics and allowing the driver to raise or lower the windshield, the team discovered it was possible for a driver to look out of an open gap while rain and snow were somehow redirected from entering the car.

If anyone can explain how this would have worked…I am all ears! Though it adds up as a very simple car, they were far from finished with quirks and features.

Prototypes were equipped with front-wheel-drive, with the driver and passenger sitting on the company’s snail-like 425-cc engine…borrowed from the 2CV. From the larger DS (and later the Coccinelle-sized GS), hydropneumatic suspension was fitted, with two spheres for the front wheels and one for the rears.

Inside, seats cushioned with thin plastic wire ensured nobody would mistake it for a luxury car.

All of their ideas were had a purpose to them: the team wanted to modernize the (then) mainstream compact car — in a world dominated by the VW Beetle, Fiat 500, BMC Mini, and 2CV.

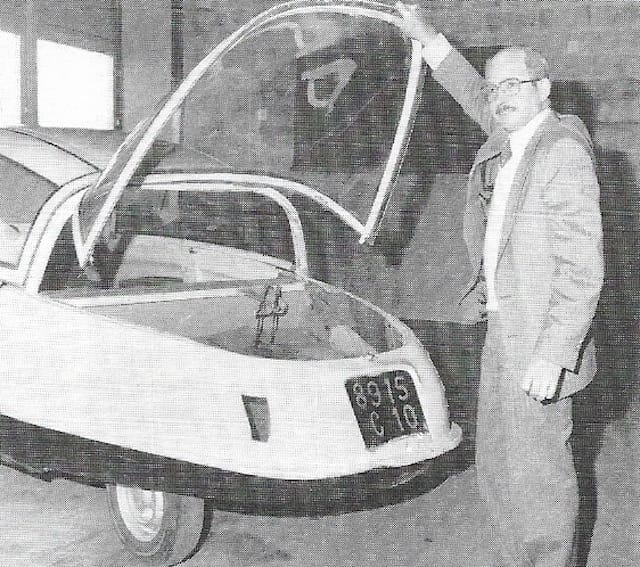

The final prototype of 10 built in total, the C10 weighed in at 382 kg (842 lbs). Its shape, weight, and 12-horsepower engine gave it a top speed of, incredibly, 110 km/h (68 mph) and fuel consumption figures as modern as the typical hybrid: less than 5 L/100 km (50 US mpg).

May I remind you: this is 1956. A much larger 1957 Chevrolet sedan would be closer to 17 L/100 km (13.6 US mpg), while a Volkswagen Beetle of that era was good for approximately half of that, at 9 L/100 km (26 US mpg). At 5 L/100 km, the Coccinelle was a huge leap forward in claimed efficiency.

Pray we don’t need to live through two world wars, as Lefèbvre did, for our engineers and automakers to rediscover the idea of intelligent, deliberate — clever — austerity.

Lefèbvre’s leadership and atypical ideas meant that once his moonshot machines were produced, the models had to live on the market far longer than their more disposable competition — at least in the design sense.

From first sketch to final prototype, I figure it took about three years to get the C10 out the door. Others say the progression from first to final prototypes took as little as a year, but I think that is a bit quick…let me know in the comments if you have references or source material that can help me establish a more accurate timeline.

To put this in perspective, consider how quickly a modern Chinese car company with a small army of dedicated staff can now design and produce a model.

Electronics giant Xiaomi recently went from the announcement it would start developing cars to the reveal of its first production car, the SU7, in 1,004 days(!!) Not impressed? The company has developed its own casting method, its own alloy named Titan, and plenty of the other crucial stuff like the bodywork, software, an interior, and the driver assistance tech that, y’know, goes into a 2025 car.

Back to Lefèbvre in a very different situation, with the resources of a resurgent Citroën but only five sets of hands. Frankly, the effort seems cooly disconnected from the rest of the company—were they simply allowing the ‘old timer’ something fun to do before his retirement?

Sadly, as the last prototype was nearing completion in 1956, Lefèbvre fell ill and became partially paralysed on his right side due to the effects of hemiplegia — possibly after suffering a minor stroke.

Ever the innovator, he then taught himself to draw with his left hand.

Just six years before his death, he left his post at Citroën, retiring to the small L'Étang-la-Ville commune about 40 minutes west of Paris. Even though it was never shown publicly in period, Coccinelle C10, the final iteration, has been retained by Citroën since the project ended in the late 1950s.

It’s an impotent but acceptable show of respect for Lefèbvre’s last creation, considering General Motors in its prime would have sent the team’s every last drawing, prototype, and half-eaten baguette to the crusher while they stepped out for a smoke.

Is the Coccinelle concept an irrelevant idea from a bygone era? Consider that maybe we’ve only now caught up to this genius.

Think of what the popular Citroën Ami’s low-cost design and low-speed electric motor could do in a more slippery, highway-focused shape. I can only hope that Citroën dusts off its Coccinelle prototype, replicates it with modern materials, adds Ami EV running gear, and allows for a reborn ladybug to have some time in the sun.

If you’d like to know more about André Lefèbvre, check out the book ‘André Lefebvre, and the cars he created at Voisin and Citroën’ by Gijsbert-Paul Berk. It’s even in Kindle format, so no excuses. ;)