Colani C112

It takes talent to spend a career hustling to the point where your real-world, earned knowledge of design and aerodynamics provides enough gumption for building your own car designs, free from most restrictions.

Race cars have rulebooks to follow. Production cars must conform to many regulations. Look long enough and you’ll discover it’s a problem almost everywhere: even original Hot Wheels designs are expected to perform on a Hot Wheels track.

Being devoted to weird cars, I’ve already written about several scratch-built cars on this newsletter, but only one to date by the outsider’s outsider, Luigi Colani.

Instead of giving you a history lesson, I’ll promise to chip away at his story over the next few years, through the vehicles he’s designed. Why spoil the surprise(s)?

Hey, you: think modern car designs are trash?

These days, it’s possible to use A.I. to generate your own ideas for vehicles, and potentially earn a small profit from the views this “work” has generated. Tag it properly, and there’s no doubt it’s more likely that a member of the official design staff stumbles upon your “work” and have strong opinions about it.

As if it needed to be said: A.I. ain’t following crash test regulations when it spits out a playful render based off of some prompt. To the corporations making money from subscription fees, software integrations, and buyouts, we are the useful idiots.

In contrast, when Luigi Colani thought cars were shit, he went out and built his idea of a better one. Not like coachbuilt cars for clients, or in YouTuber-style builds, mind.

Colani’s career out of school had started in the U.S. after being head-hunted by a military contractor, which he left after being head-hunted by a certain French team hoping to win the Index of Efficiency at the 24 Hours of Le Mans with its ultra-aerodynamic coupés.

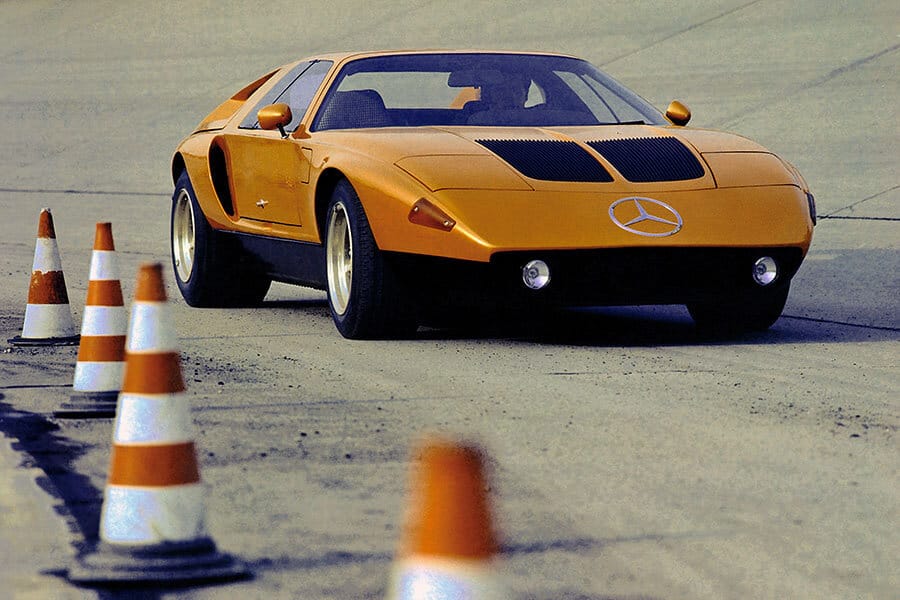

Mercedes-Benz promotional photos of the C111 • Mercedes-Benz

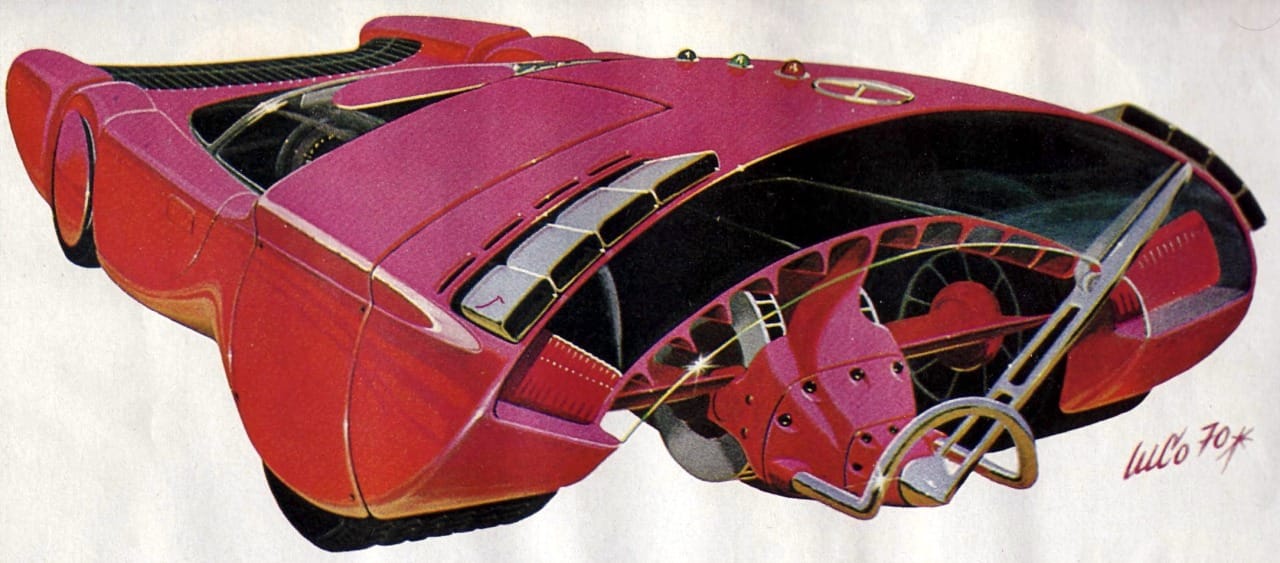

As the story goes, when Mercedes-Benz presented its first rotary-engined C111 coupé prototypes in 1969, Colani was so incensed by how conventional it was that he applied all of his talents to this full-size design mock-up called C112.

Don’t get me wrong: there are plenty of car companies and builders out there who are capable of making a car from scratch.

Few make cars, seemingly, out of spite.

I adore this about Colani.

Colani C112 in the Colani facility • source unknown

At first glance, it’s easy to dismiss this as some quack job’s lawn sculpture, but its exquisite detailing and highly sculpted form — with its mock-up mechanical parts in the right places — point to a more horrifying conclusion: humans are meant to fit in the form, not the other way ’round.

Colani is quoted as having called himself a philosopher in 3D, and I’ll take his word for it. (Given society’s recent love of liars, I’d say our designer’s claims are comparatively saintly.)

Perhaps Colani saw the Mercedes-Benz as just another image-driven design meant to fluff up fragile male egos, because he’d already learned that the most effective tools for performance-enhancing cars was to lower weight and / or aerodynamic drag.

More speed, more stability, more efficiency — at the impossible cost of trashing the three-pointed star’s image.

I think Mercedes-Benz couldn’t follow that path because its customers are people, not drag coefficients, and wasn’t willing to burn profits and/or corporate capital in order to challenge race or road regulations.

If the decision-makers didn’t already feel as though Colani’s proposal was too curved away from the Stuttgart brand’s guidelines, the passionate outsider painted it a shade of pink I’m christening as Bonneville Land Speed Record Barbie*.

I hope it was meant to be both spiteful and dramatic.

If so, mission successful.