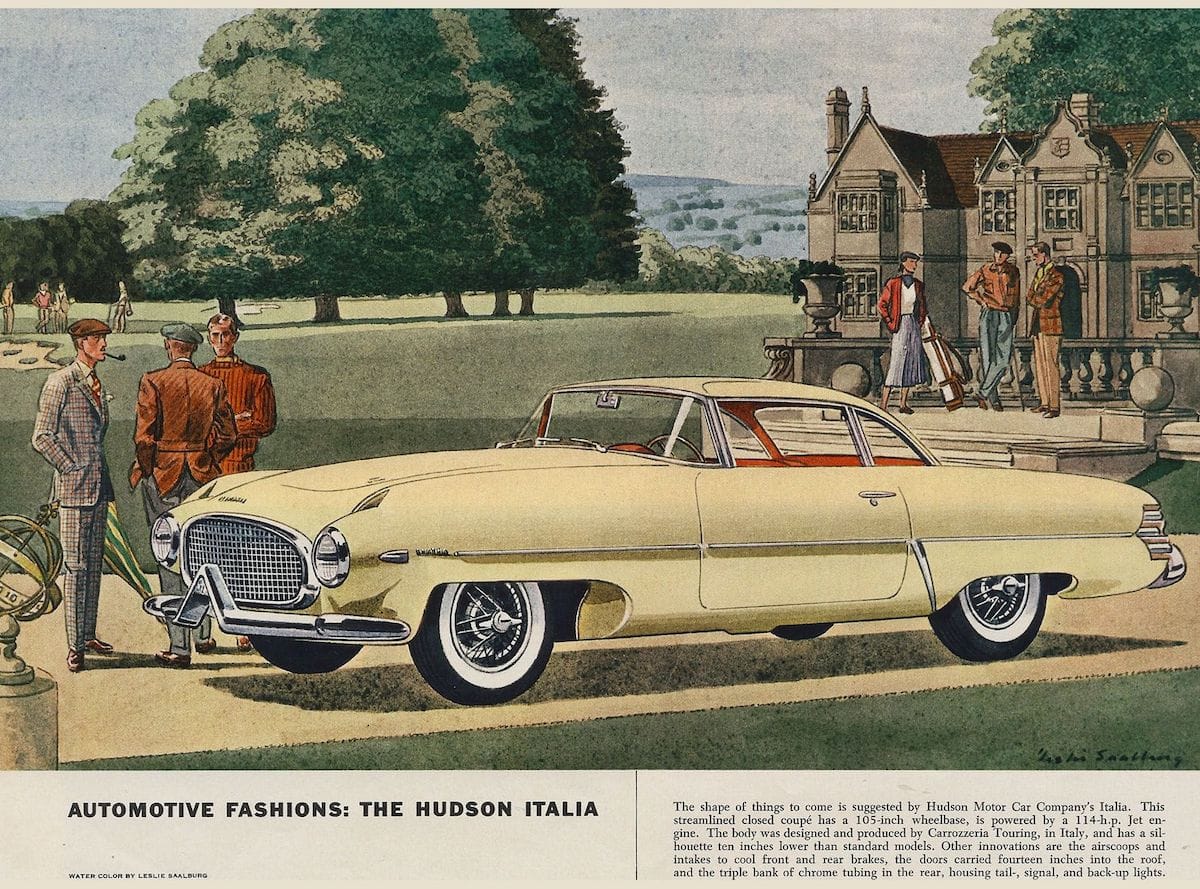

Hudson Italia by Touring

This isn’t going to be a story about the downfall of Hudson, or the merger of the company with Nash-Kelvinator to form American Motors. I can’t and won’t wax on about Hudson’s final days as an independent automaker.

What you should know about the downfall of Hudson is that the Big Three automakers in the 1950s had the production base, designers, dealerships, and marketing to put huge numbers of North Americans in cars. This came at the expense of the smaller, so-called “independents”: Packard, Hudson, Nash, Willys, Kaiser, Studebaker, and Crosley.

These automakers simply lacked the resources (often: production capacity, engineering speed, dealer network) to compete, and all would be dead by the mid-1960s.

Before their heat death, the 1950s were when the independents were really scrambling: new ideas, new features, new technology, new styling, anything to grab a slice of the market.

It’s in this atmosphere that Hudson’s lesser-known design chief Frank Spring was working.

The Hudson Jet, launched in 1953, was styled based on the lesser of three designs he’d offered. Spring had submitted two striking ideas for a small car, and a third that incorporated suggestions from management and dealers.

Number three it was, then.

Some accounts say that Spring was more like General Motors’ Harley Earl, an idea man who knew what he wanted, but not necessarily comfortable with producing endless sketches in the design studio.

After Spring’s preferred Jet designs were ignored — he was furious, by the way — an increasingly desperate management threw him a carrot: take the Jet engine and chassis and make a halo car.

No pressure.

Off to the Brussels Motor Show Spring went, to meet with Carlo Felice Bianchi Anderloni, the head of Carrozzeria Touring. Over a shellfish dinner near Brussels’ Grande-Place they drew Italia’s first sketches on hotel napkins.

For the prototype, a Hudson Jet was shipped to Italy, and Touring applied Superleggera bodywork. Before the term was plucked from the past by Lamborghini as a sexy-sounding trim package, it was known as a unique method for then-lightweight construction.

Traditionally derived from the construction of fabric aircraft, here, a series of small diameter tubes create the outline of the body, while thin alloy metal panels are attached to the tubes to cover the body and give the structure strength.

Hudson Italia models in production. • Touring / Hudson

The resulting Italia was a sensation: fender-top brake cooling ducts, rear lights mounted in chrome tubes, mesh grille, doors that cut into the roof. Compared with the Jet, the Italia’s roofline was about 10 inches lower.

And check out the rear fender detailing, with hand-formed metal ‘exhaust pipes’ housing its brake, reverse, and indicator lights.

Spring finally had his show-stopping design, and Touring was contracted to build 25 more cars.

In many cases even today, automakers will ship rolling chassis, or the engine, brakes, frame, steering, suspension all as manageable sub-assemblies to minimize assembly time in a local production facility.

Hudson didn’t do that, though: it shipped the individual component parts to Italy! This meant it was a hand-made Italian-American car, which very rarely turns out well.

Touring also had to sub-contract the mechanical assembly to a small workshop nearby.

By the time the work was completed, and the car was shipped back to America, Hudson (the company was effectively dead.

It was a struggle to sell the 25 cars made. The Italia had a weedy 3.3-litre straight-six engine with barely 100 horsepower. The Italia was only officially available in a cream colour, with contrasting cream and red interior.

Also, the car sold for 20 per cent more than a Cadillac in 1955, from an automaker that couldn’t sell its more basic models. Replace with any brand from more recent history, like would you have bought a $100,000 Scion, Saturn, or Daewoo?