Opel Eco Speedster

Don’t know about you, but I’m tired.

I’ve been tired for a long, long time. So tired, in fact, that for the better part of a decade I’ve been content to watch the car world descend farther and faster into a shimmering pool of stupidity.

Annoyingly, for me, what bothers me most isn’t specific product decisions or pundits blowing hot air all over manufactured “EV vs gasoline” and “gas vs diesel” debates.

It’s a lack of common sense and critical thinking. I don’t expect you (or anyone) to know much about cars, all I ask is that you consider the immutable laws of the universe before opening your mouth…tapping out a comment on social media…whatever.

The less energy it takes to move a vehicle, the less energy (gasoline, diesel, Kw, propane, and so on) it will take to fuel it.

Three huge benefits:

- Less energy used in operation means less cost for the driver;

- Less strain on energy production;

- Fewer emissions — less fuel burned, less undesirable gas out

Because drivers are responsible for fuelling their own cars, manufacturers only have to meet regulations (that they lobbied for anyway) and ensure it’s not a $500 charge every time you visit the pump — specific L/100 km or MPG matters little to most people.

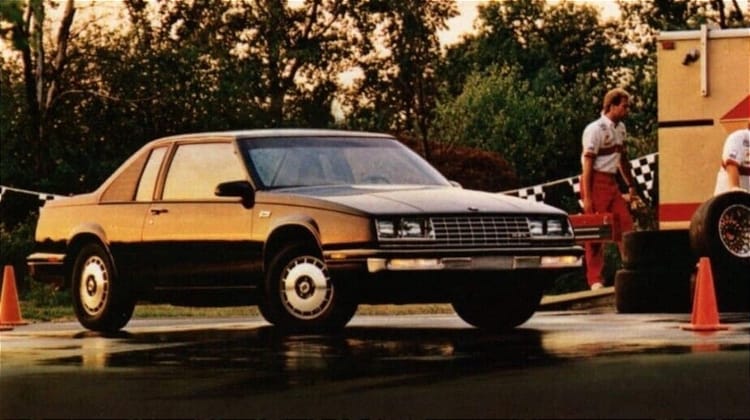

Official publicity photos of the Eco Speedster without its final livery. Note that it used an automated manual transmission, too! • Opel

As the connection between burning fuel and emissions is nearly impossible for us to see without specialized equipment, it’s not intuitive to connect fuel spent with gases emitted.

Partly, this is what killed diesel engines in most of Europe, where manufacturers were adding weight and complexity with consumer-facing features, trying to balance these niceties with more advanced mechanical systems (high pressure pumps) and computerized controls to keep emissions at acceptable levels.

Electric cars make way more torque than diesels, are quieter, and have no direct emissions on their surrounding environment (besides tires and brakes).

Still — diesels don’t have to be large, powerful, tuned for performance, or all that terrible for the environment relative to private jets, cruise ships, and hypercars.

Let the people have their miserly 1.3 liter diesels.

Until people demand more, automakers will be oh so content to maintain the status quo. I don’t blame ’em, but I don’t have to like it.

Anyway, what I want to ask is this: would a diesel be so bad if it was capable of using less than 3L / 100 km (78 U.S. mpg) of fuel, traveling at road-going speeds…so long it was still capable of reaching more than (155 mph)?

Opel thought it could do better. Its targets for the Eco Speedster were 2.5 L/100 km (94 U.S. mpg), with a top speed of 250 km/h (155 mph)…though not at the same time.

After the high-speed portion of the test was concluded, engineers learned the car did an impressive 8.9 L/100 km (26 U.S. mpg) — while averaging more than 240 km/h (150 mph) on a high-speed test track.

Opel Eco Speedster in action. • Opel, Car and Driver

Equipped with a 1.3 liter diesel co-developed with Fiat and used in, like, three dozen different vehicles — ever hear of the 1.3 MultiJet? — this Lotus Elise-derived Opel Speedster test bed proved it’s possible to have speed, style and efficiency.

Engine horsepower? About 110. Torque? Less than 150 ft-lbs (200 Nm).

We don’t have to guess at how Opel’s test went, and those who know the story are probably wondering why I’m about to leave out certain details of the Eco Speedster’s high-speed run, such as its transmission oil burning up and computer problems.

Because this newsletter is not for clicks, and I’m not writing for some SEO-minded purpose, I can simply link out to a well-written story in Car and Driver by a writer who was there, Tony Swan (d.2018).

For the younger among us, I noticed this little nugget in Tony’s article:

“The only hiccup in my run occurred at the end, when I came down off the banking a little too hot for cold brakes and realized I wasn't going to be able to negotiate the serpentine pit entrance. I picked up the throttle and went around again.

“No problem—at least not just then. However, Chris Harris, the British writer following me in the rotation who had witnessed the whole episode via radio communications, managed to duplicate my error, then compounded it by trying to wrestle the car into the pits anyway. He was rewarded with a spin, and the car whacked the hefty pit-lane marker lights, rearranging some of the carbon fiber.